Time-boxing is good. Sprints are bad

In software development, adopting Sprints was never a path to agility and flow: It was yet another wrong turn

So-called iterations, or Sprints have been one of the key ideas the Agile movement leaned upon since its beginning. Conceptually, this idea is hardly better than the Waterfall logic that Agilists have tried to overcome.

During the 2000s, thinking among software development professionals around how to best organize the production of products shifted: Software companies started to abandon so-called Waterfall logic, i.e., project management with month-long project phases and cycles. Instead, they began to move towards the logic of Sprints: regular, steady iterations that would usually take just 14 days – in some cases a week, or maybe three. As we will see, moving from project to iteration logic was a classic case of jumping out of the frying pan into the fire.

The problem: just like traditional project management and phase-gating, Sprints are yet another opposite of flow, lean, and agility. To understand this predicament better, let’s briefly turn to the historic origins of lean philosophy: The concepts of the Toyota Production System (TPS). Here at Toyota, between the 1950s and 1970s, production processes were transformed from serial, or batch processing to the principle of single-piece flow: a principle in which each individual workpiece is its own batch – without the accumulation of larger series and batches, and without complicated scheduling or forecasting. Single-piece flow was the key to just-in-time production, the overall elimination of inventory, and the end of sophisticated steering at Toyota.

But back to Sprints. These iterations bear no resemblance to the Toyota principle of single-piece flow. Rather, they resemble medium- or large-scale series or batch processing. In other words, Sprints are akin to the type of production that Toyota tried to overcome, substituting it with just-in-time and flow. A 14-day sprint is akin to managers in an industrial company announcing to the production department that

“from now on, production must always be carried out in series that will take exactly 14 days to complete – with as many individual production units included in one batch as fit into the 14- day period of processing.”

The number of individual production units would somewhat vary from run to run, with the main target to be concluding every batch within 14 days! Such an announcement would be insane: It would result in shrugs, regardless of whether batch or flow logic was employed. It would subsequently cause a mind-numbing amount of wasteful activity, including intense planning, scheduling, coordination and re-adjustments.

The same applies to Sprints.

How can things be done differently and much, much better?

Truly lean-agile software development would not group individual production units into Sprints at all. Instead, it would allow the individual units (which we call items) to flow, through time-boxing of the individual items. The great Ernst Weichselbaum condensed this fundamental insight into an excellent guiding principle – without a word too much:

“Letting things flow is better than grouping them.“

Ernst Weichselbaum

The practical problem with accumulated Sprint batches can be easily recognized by its symptoms. In Agile software development, and when thinking and working in sprints, there is constant talk of planning, estimates, forecasts, weighting of items, scheduling, delays, corrections, and carryover into the next Sprint. There is almost never any talk of “smoothing” demand (heijunka), or talk of continuously reducing throughput times – i.e., typical aspects of working on flow, as is customary and necessary at Toyota and generally within Lean. In Agile software development, the focus is primarily on “completing” the sprint, on control problems, and on holding meetings – which must take place either daily or following the cycle of Sprints. In Agile scaling, this batch processing is taken to extremes, by applying multiple levels of consolidation. It’s very similar to how people in industrial production talk about their struggles in batch processing and manufacturing of large series. This relates to another guiding principle we have the great Ernst Weichselbaum to thank for:

“Better organize punctuality than manage delays.”

Ernst Weichselbaum

The concept of aggregation into Sprints has a number of consequences. Through Sprints and scaling frameworks, the Sprint itself has become the object of attention for managers and for self-proclaimed agilists. Instead of focusing their actions on the system and individual features, and continuously improving throughput and the flow of work (Kaizen), the management of Sprints has become the work domain of people with titles such as PO, SM, and Agile Coach. Developers, in the meanwhile, were demoted to spectators of the agile theater surrounding the Sprints.

Sprint accident: Iterations fail to time-box the work

From a conceptual point of view, Sprints, regardless of their length, are never a good idea. Upon closer inspection, Sprints turn out to be fundamentally “un-agile,” “anti-flow,” and “anti-lean.” Which brings us to a wider problem in the software development industry. Scrum, arguably the most successful approach to agile software development, is inconceivable without Sprints. The Scrum approach developed by Ken Schwaber and Jeff Sutherland relies entirely on the effective management of Sprints through all kinds of visualizations (boards), rituals (reviews, stand-ups, retrospectives), and roles (Product Owner/PO and Scrum Master/SM). One could say that Scrum knows no other method than that of summarizing. Nothing has changed in this regard over the last three decades with Scrum and millions of certified Agilistas. It should be noted that the Kanban approach to software development doesn’t fare much better, even though it does not rely on Sprints. Sadly, most Agile approaches rely on batches, or Sprints, on planning and grouping, one way or another – at least up until now.

Every person whose success depends on software development should ask themselves today, almost 25 years after the creation of the Manifesto for Agile Software Development: Do we really want to finally achieve agility, lean, and flow in software development, or do we want to keep pretending?

Instead of grouping, let items flow through the OK Point

To overcome the Sprint problem, I propose the following guiding principle in the style of Ernst Weichselbaum:

“Better work on software in a time-oriented manner

than sacrifice time for working on Sprints.”

Niels Pflaeging

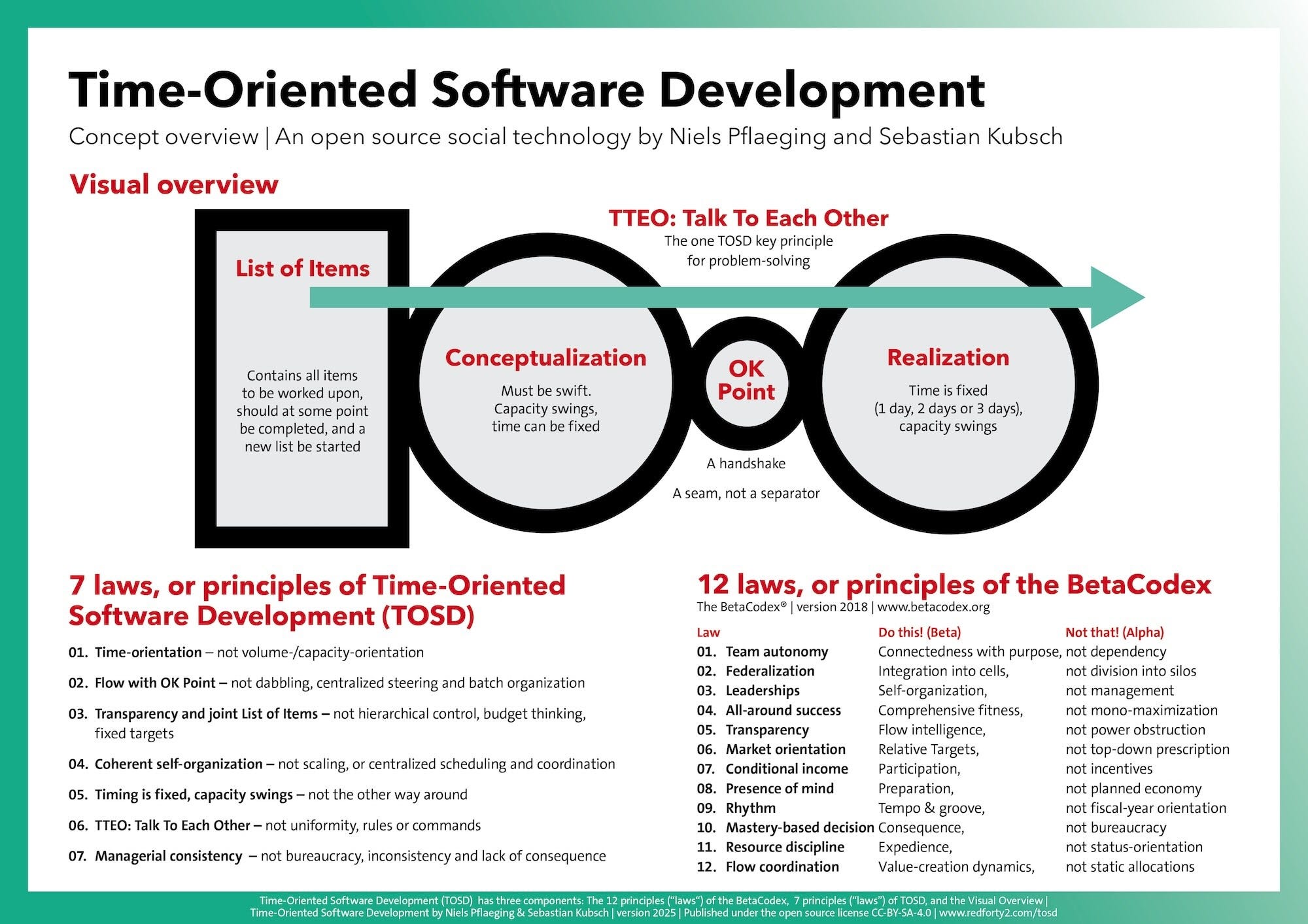

This guiding principle sits well with the Time-Oriented Software Development (TOSD) approach. Because in software development, just as in industrial manufacturing, the key to agility, speed, punctuality and leading cost lies in creating flow by submitting the work to the primacy of time. Accordingly, in TOSD, there are neither Sprints nor iterations. There is no planning, no estimating, no forecasting, no centralized scheduling and control, no re-scheduling, and no centralized coordination. This allows everyone to focus on the work itself, and thus on producing output (a.k.a. working software).

Development teams do not exist in TOSD either. There cannot be any development teams, because such teams would be yet another form of grouping and accumulation that would create further obstacles to flow, leading us to two key aspects of software development work:

1. It’s not “iterations” that should be time-boxed, but the work itself.

And:

2. No piece of software has ever been produced by a team.

All software is produced by an individual developer or a pair of developers.

No more, no less.

To add a touch of A.I. infusion to this article and to our reflection on TOSD practice, here’s a highly accurate quote by TOSD co-creator

, CTO at Pradtke GmbH, about the relationship between A.I. and software development.“It’s not that ‘A.I. will replace all or most developers.‘

Instead, developers using A.I. will replace all or most developers that don‘t.”

Sebastian Kubsch

So how does Time-Oriented Software Development (TOSD) actually work? In TOSD, each work item has its own, and always very short flow rate of up to a few days. Ideally, this is just one to two days. It can be up to four or five days, but no more than that. In a time-oriented work system, everyone involved in software development works together with a view to creating and maintaining an uninterrupted flow of value. It’s not centralized or specialist roles that take care of coordination, but the coordination is done as an ensemble.

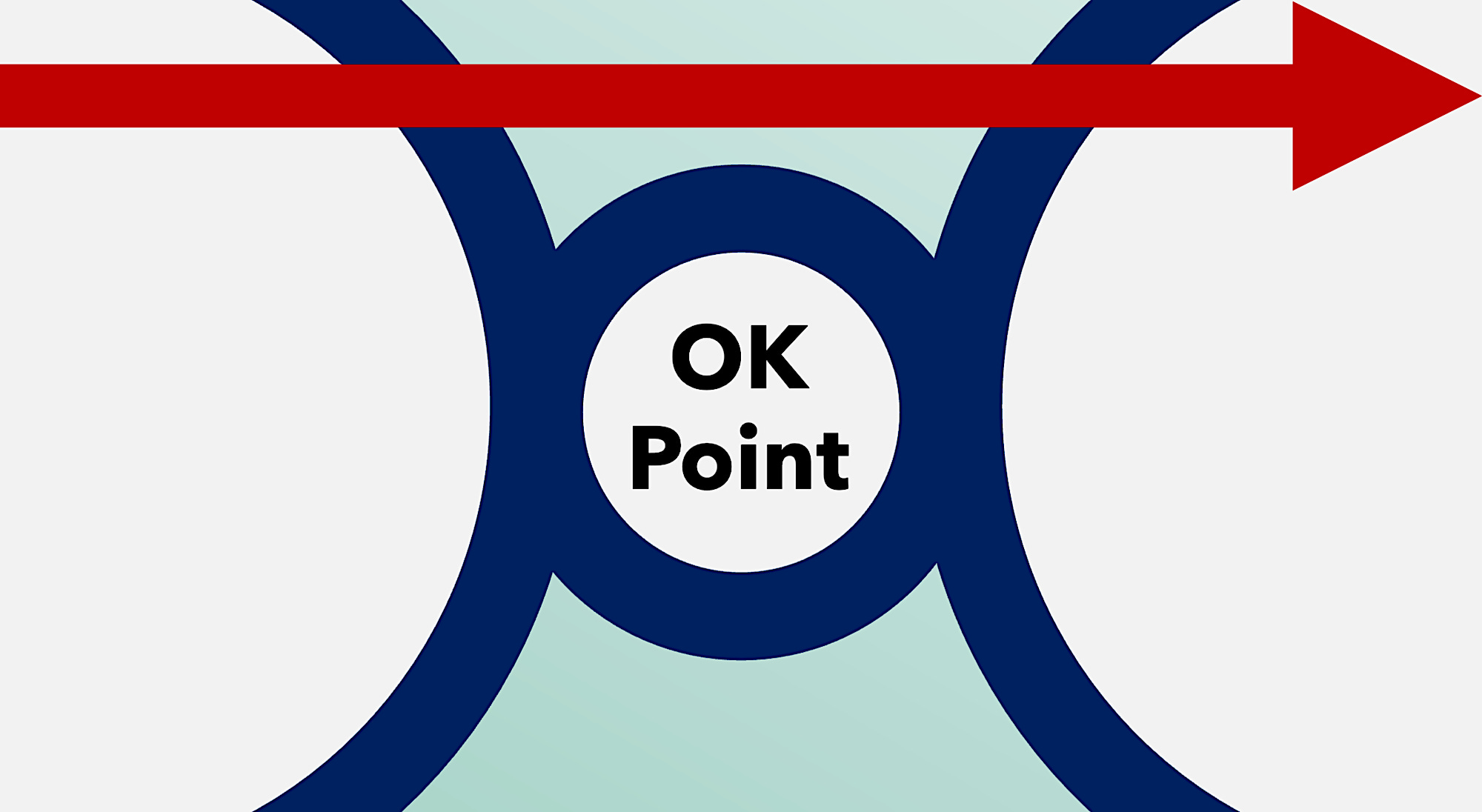

Time-boxing of individual items is possible through a novel device, the OK Point, which separates Conceptualization of an item from its Realization. Every item flows from a List of Items to Conceptualization, passing through the OK Point, which also provides for a handshake between Conceptualizers and Realizers of the particular item. Realization is always strictly time-boxed, Conceptualization can be time-boxed, too, depending on the available level of mastery.

Time-orientation makes babysitting dispensable

This brings us to another difference between the well-known approaches of Agile software development and TOSD. In Scrum and other Agile methods, developers are not expected (or demanded) to be prudent and to develop a view of the big picture. Unfortunately, in those methods, having such expectations towards developers is often considered unrealistic or utopian, even. “Our developers just don’t want to concern themselves with anything beyond their beloved programming!” is a common refrain. And: “Those people hate communicating, they just want to code.” is another. Accordingly, roles like PO SM, and Agile Coach end up being held responsible for thinking, communicating, steering and centralized control. It is as if they were replacing the defective brains of developers, or being employed as babysitters.

In comparison, in a time-oriented system, everyone can (and in fact must) be expected to take a cautious, alert view of the whole system. It goes without saying that thoughtful consideration can be demanded of everyone – just as alertness and kaizen activity are expected from every worker at Toyota. Why can’t the same be expected of software developers? After all, software developers are mature, skilled and often highly educated human beings. Treat them accordingly.

In short, in order to break free from Sprint-based stop-and-go systems of development, a different view of time and flow is required, as well as a humanistic view of the people doing the work on the gemba. So that software development can finally run like clockwork.

More about Time-Oriented Software Development (TOSD)

Find out more in the brand-new research paper about the TOSD approach - written by

and .Also visit the TOSD website at timeoriented.dev, with information on TOSD services to support TOSD adoptions, and an overview over the TOSD team of associated consultants.

For the TOSD open source license, visit www.redforty2.com/tosd

Fore more on the basis of the Toyota Production System (TPS), get the brand new book What would Ohno-san do?, edited by Niels Pflaeging and

. The book contains 160+ quotes of Taiichi Ohno, the legendary architect of TPS. The book is now available in bookstores everywhere.

Pensándolo de una manera amplia, tener "equipos de desarrolladores" es equivalente a crear equipos de "vendedores" o de "torneros".

Lo que no es lo mismo que crear "equipos de desarrollo", que tienden a ser multidisciplinarios. Eso abre un poco más la idea del ciclo de vida completo o el "End 2 End" como se le suele llamar, contenido en el equipo completo.

TOSD va un poco más allá: donde no necesites equipos, no los crees. Hacerlo puede burocratizar de manera muy penosa la creación de valor y la entrega en tiempo.