Placing software development in the hands of ‘development teams‘ is a bad mistake

Software development teams should never have existed: They are a misunderstanding turned structure

The truth about the nature of software development is somewhat simpler than what complicated approaches such as Waterfall project management, or brainchildren of Agile like Scrum, Scrumban or Kanban have us believe.

One thing I have learned during the 20 years that I have been part of the Beta, Lean and Agile movements, as a speaker and consultant: People don’t question their assumptions nearly as much as they should. One example of this is the core Agile notion that people dedicated to software development should be grouped into development teams, into Agile teams or Feature teams: Some kind of cross-functional group focused on product development alone. It’s a sticky belief inherited from a time when all software development was undertaken in the shape of projects – applying project management techniques. Or what techies have come to call Waterfall methodology.

Faith in the need for dedicated development teams from the Waterfall era survived the Agile upheaval: In fact, it was very much sustained and strengthened. Since 2001, when the Manifesto for Agile Software Development was written up, many tools, frameworks and fads have successively built upon the belief that development teams are a core ingredient of Agile development, and of software development per sé. Problem is: That notion is wrong, and not just by a notch. The belief that

“software is built by teams”

is itself not just profoundly flawed, it is completely lacking evidence. Consider that empiricism and being empirical is what that Agilists have always claimed to adhere to, since the beginning of the Agile movement. The observable reality is different, though: It is that software is not created by teams. It is never created by teams. We will come back to that in a moment.

To be clear: This text is not about mere choice of vocabulary, about subtle distinctions or about the use of words (sometimes confused with linguistics). Instead, this article elaborates on aspects of Time-Oriented Software Development, TOSD and seeks to address the structural problem of how to organize product development effectively and correctly – with either small, or medium, or large groups of developers. This article builds on BetaCodex concepts and especially on Cell Structure Design, a concept that Silke Hermann and I have researched and brought to life as consultants with dozens of organizations, including a great deal of tech and software firms, between 2008 and today. In 2025 alone, we as Red42 advised two software companies that abolished development teams, largely integrating developers and software development into their periphery, or business cells.

But let’s get back to the state of mainstream software development in the here and now. Based on new research paper by Fiona Chen and James Stratton of Harvard University, who examined the productivity of programmers using AI, an article by the study’s collaborators from Jellyfish concludes that effectiveness of software development rests upon appropriate organizational structures, more than anything else:

“Coding isn’t the bottleneck. For many teams, the limiting factor on delivery isn’t how fast code gets written – it’s requirements gathering, design decisions, code review, testing, deployment, and coordination across teams. Making the coding step faster doesn’t help much if work is stuck waiting on upstream or downstream dependencies.”

The study found that productivity improvements aren’t yet translating into the business outcomes that actually matter. It is fair to conclude that what limits software development performance is not “slow coding that needs to be accelerated by AI”, but (1) how non-coding development tasks are embedded into the process and (2) coordination & waiting times. Put differently, research suggests that AI-improved coding alone won’t get us out of the mess of dysfunctional organization of the development process. Which means we’d better get to continuous flow in development now. This, in turn, requires the end of centralized coordination and of stop-and-go in software development. Both of which are impossible to achieve in the logic of Waterfall and Agile-as-we-know-it: Waterfall and Agile are not solutions to the mess – they are part of the problem.

Back to the dogma about teams developing software. While this core belief has led to the creation of development projects, development departments, product functions, silos and “teams” of many shapes and sizes, that belief is entirely untrue. Ridiculous even. In software development, the phrase “The team will take care of it” is not a strategy, but rather an avoidance tactic or the expression of imposition onto teams that’s often falsely called flexible or agile. Don’t get me wrong: Teams are great and we need them. But to impose team structures onto software development, specifically, imposes a level of complexity and complicatedness of interactions – among team members and between teams – that aren’t outweighed by any benefit whatsoever, as we will see. Still, not even Agile’s finest minds, like Ron Jeffries, whose insightful book on The Nature of Software Development I reread recently, have thought of questioning the dev team dogma. It appears that roughly 100% of people in Agile today take the notion for granted that dedicated development teams are the way to go. You, dear reader, are likely to believe that claim, too.

A more productive way of thinking about the nature of software development

I would like you to dare a tiny thought experiment first. Suspend disbelief for a moment and fool yourself that you think the sentence is true:

Teams don’t build software.

A team is far too big to develop any single piece software.

Consequently, we don’t need development teams at all.

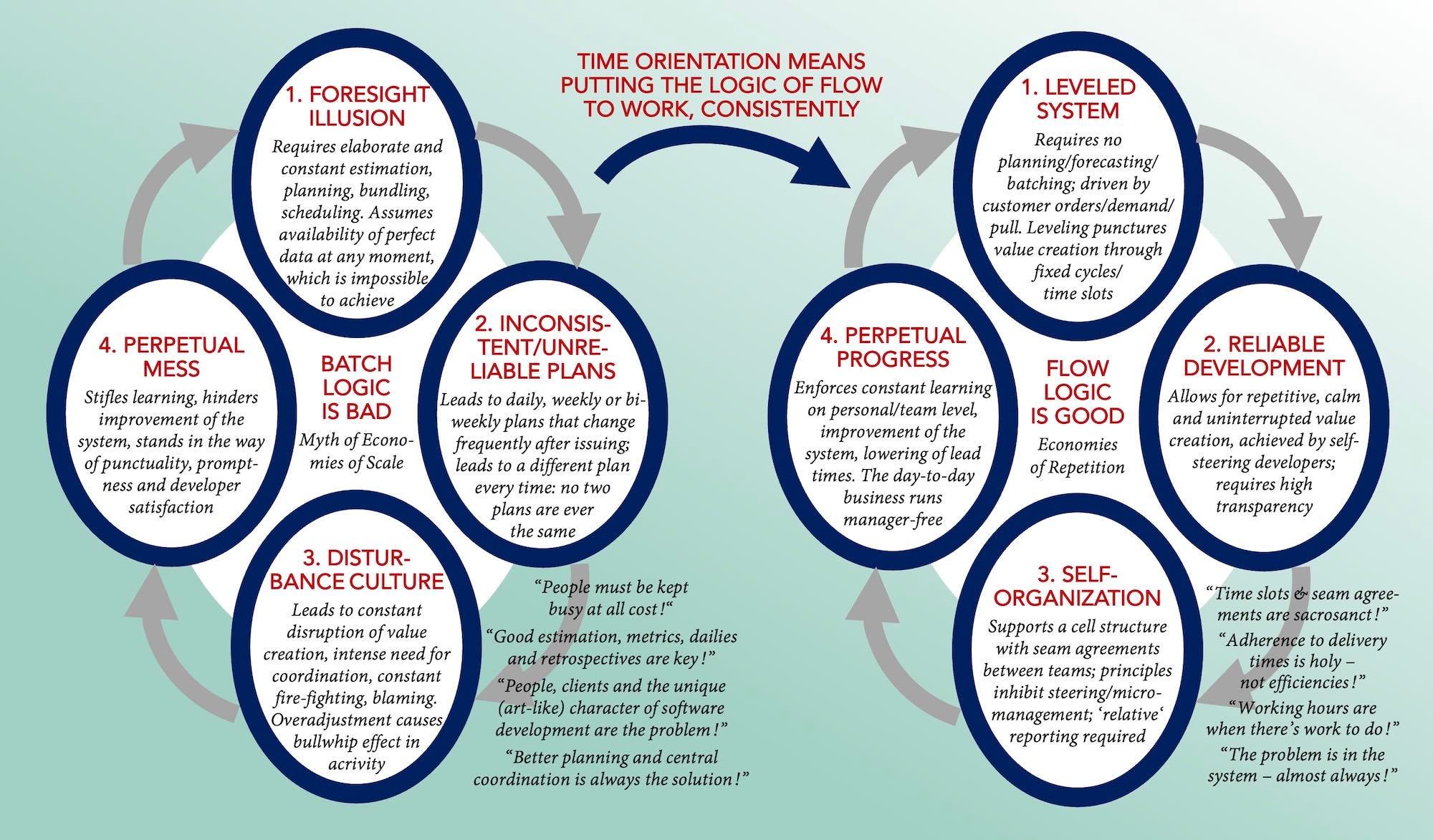

Tried it? What if organizing developers into development teams is a common, but also powerfully obstructive way of batching development process and items, usually on top of grouping and batching that’s imposed on the process through cadences, iterations and Sprints. Development teams maximize all kinds of problems of coordination, shoddy process, sloppy decision-making and futile waiting times. It’s a recipe for waste. Under such circumstances, it is impossible to produce flow and fulfillment (see left side of the illustration. The logic of flow requires a completely different kind of logic (right side of the illustration).

An alternative to “teams that build software”

The conclusions above about the messy state of software development today, with all the steering, the need for coordination and excessive waiting and stop-and-go dynamics may be quite straightforward. At least to those who have been in software development for some time. The alternative to Waterfall and Agile beliefs around “teams building software” isn’t so obvious, though. It is counter-intuitive, and you, dear reader, may initially respond to that alternative by thinking: “Haven’t I always done things that way?” Problem is that you likely haven’t, or at least you haven’t acted accordingly, when dealing with development, or when organizing development. Because of our reflexive responses to alternative mental models that differ from our practiced ones, an alternative way of organizing development without development teams needs to be explained and justified, even though the reality of software development is so easily observable. The first part of a better, alternative around organizing development belief goes like this:

Principle 1:

In any single moment, any piece of software is developed by either

a single person (“soloing”) or by two individuals (“in tandem”).

Never more than that.

You may respond to Principle 1 in two different ways. One is to think that you have always known this to be true. Which is great. But if so, you should ask yourself why you (likely) have tolerated or even promoted software development teams, in the first place. Your reaction to the principle may also be: That’s nonsense – software is sometimes effectively developed by three, four, five, six or one hundred people, together. In this case I would recommend that you look closer at the reality of software development. Look at how developers work: When they work effectively, they work alone or in pairs. All work on individual work items is done ‘solo‘ or in duos (for which pair programming may serve as an example). Regardless if you find this obvious or mind-boggling, it’s a simple fact that can be observed everywhere where software is developed. Two people are enough for any task. Others might observe or watch, they might wait for work results, or they might stall the work. But you never need more than two to do the job.

Constellations of one or two individuals don’t amount to ‘teams‘, of course. As software is never developed by teams, but always by soloists or tandems, team structures amount to grouping or batching, creating barriers to performance. Developers should hook up for work on individual work items, occasionally, to form changing tandems, whenever needed. Bundling two, three or more developers together, structurally and continuously, would be an abomination, flying in the face of effectiveness, flow and developer satisfaction.

A distinction is needed to allow for an architecture in time

Principle 1 alone isn’t enough, though, to bring flow and promptness to software development, and to help us overcome the sticky, obnoxious notion of development teams, for good. We also need a concept that will structure software development in time, and that allows us to account for different inclinations among developers, for different levels of mastery and seniority – and that helps us to arrange, connect and couple non-coding and coding activities in the most effective way, without producing obstructions or delays. We need a temporal architecture for the development of software items, so to speak. This is the purpose of our Principle 2, which goes like this:

Principle 2:

Development of any single item passes through two distinct stages that need to be carefully distinguished, and connected by seam agreements:

Conceptualization and Realization.

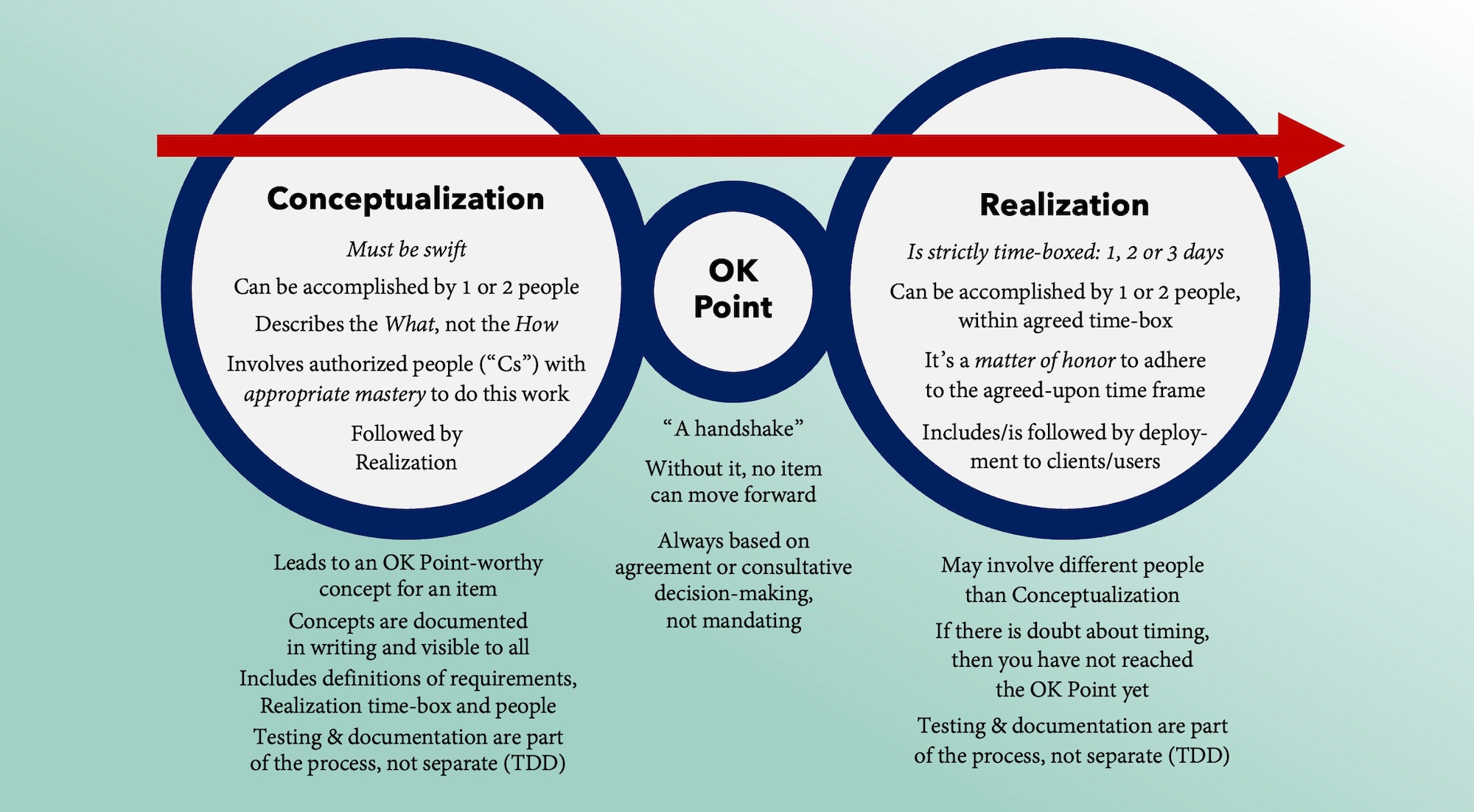

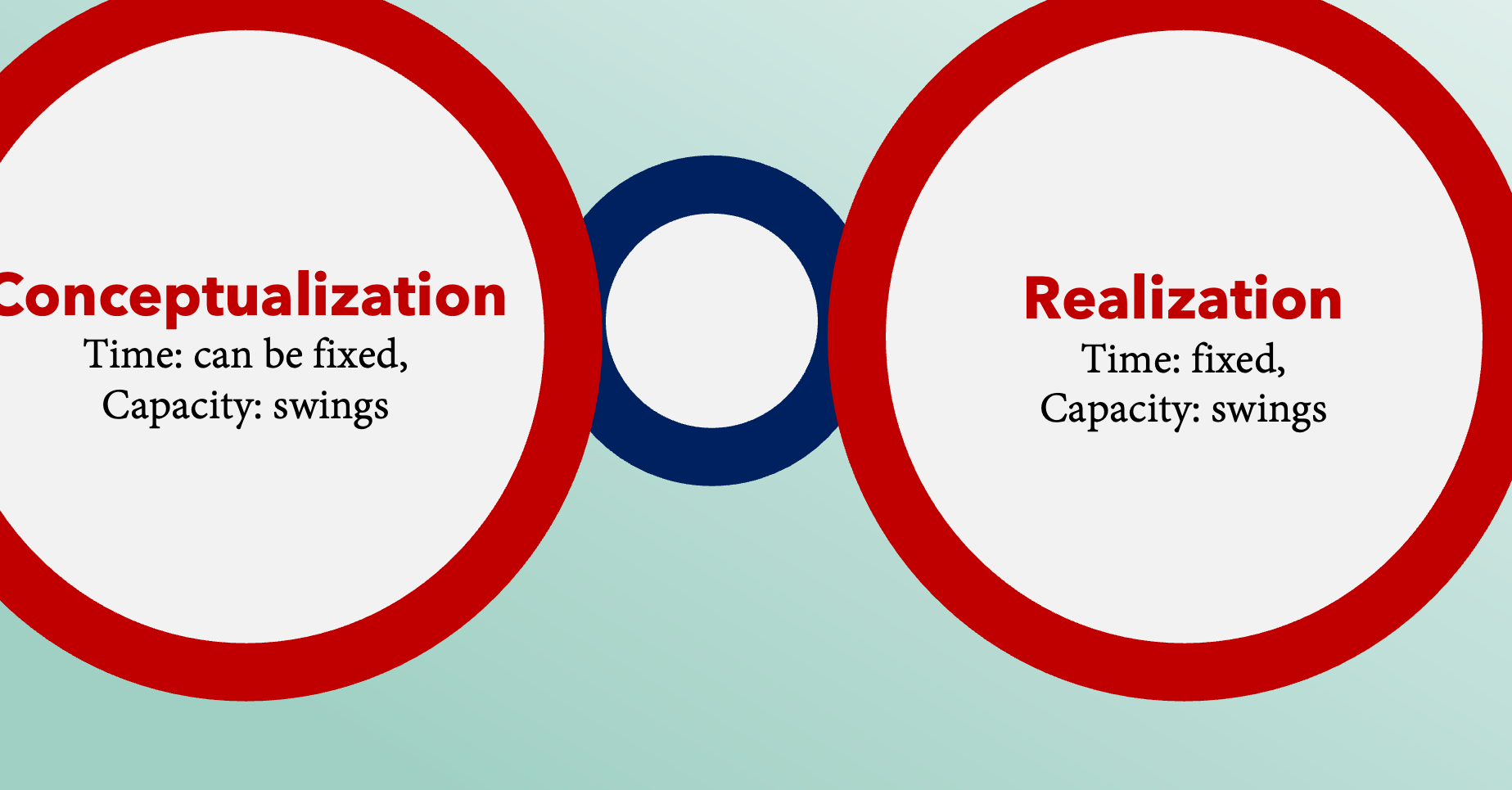

The secret to pull off software development “beyond teams” and to getting delivery times fixed, for every development item, is to distinguish Conceptualization and Realization for every single item, and by separating them by an artifice called that we call OK Point. The combination of Conceptualization (covering the boundaries, the What), OK Point and Realization (covering the How) is what enables continuous flow. What’s important is that after the OK Point, delivery time for every item is fixed - at a minimum of one day, two days or a maximum of three days. One day is ideal, as it is highly intuitive and allows for a maximum of both self-organization and transparency. For more about the structure in time of TOSD, and about the necessity of differentiating between Conceptualization and Realization in the first place, read BetaCodex Network research paper No. 26, Introducing Time-Oriented Software Development.

What’s important to know about the OK Point is that it is not an interface, but a seam. An interface divides, a seam agreement connects. Interfaces can consist of rules or structures or technology, seam agreements always consist of communication. We also call the OK Point a handshake between Conceptualization and Realization. And it should involve an actual handshake between the one or two people doing the Conceptualization, and the one or two people doing the Realization for an item.

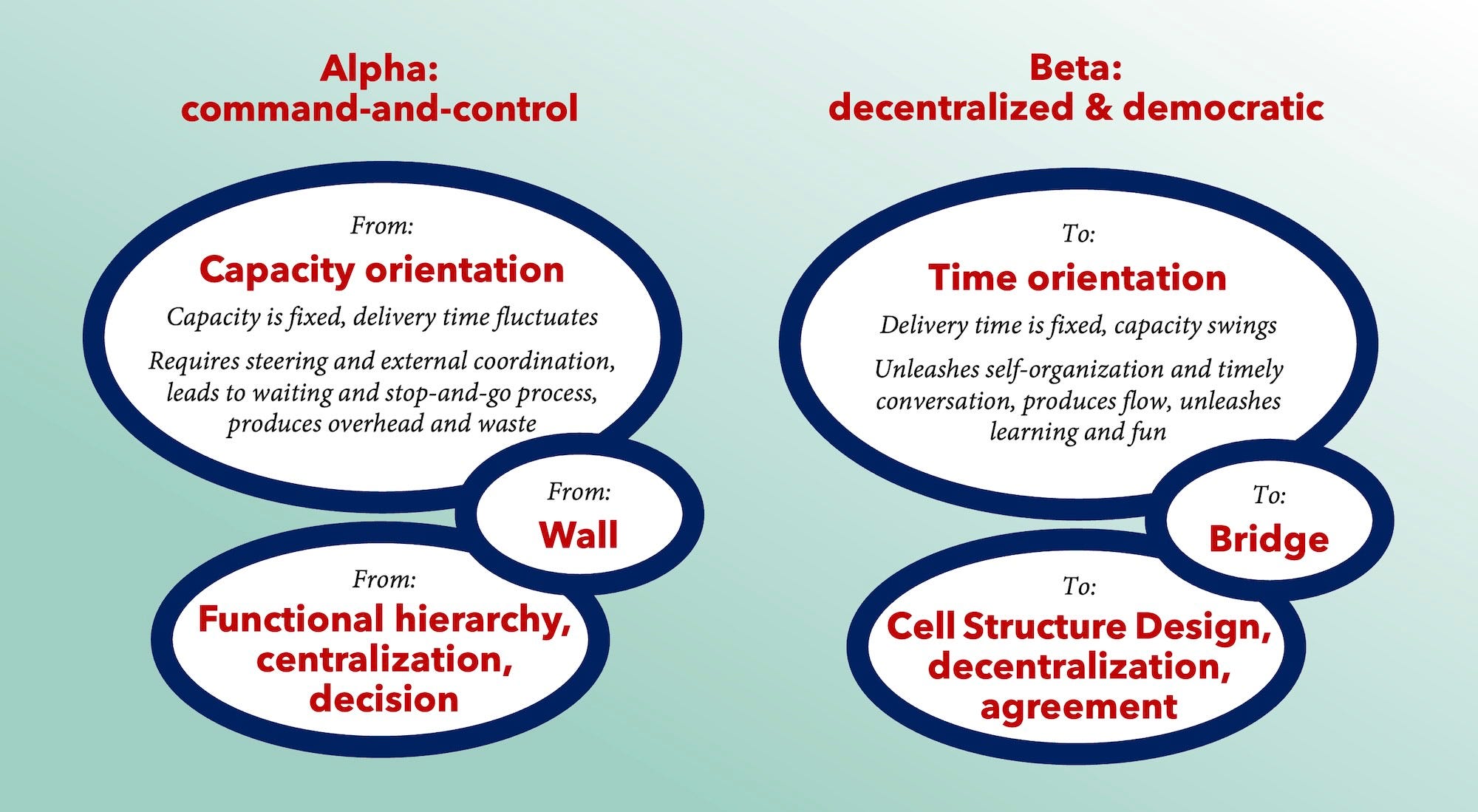

This structure in time, composed by Conceptualization, OK Point and Realization is the opposite of cadences, iterations or Sprints. In another article on this Substack, I have written about why iterations, cadences and Sprints, which are foundational not just to Scrum, but to almost all Agile practice, are a terrible idea: Such artifices amount to grouping work items into batches, which is indicative for Capacity orientation - a concept which is explained and criticized in that article. In this article here, I focus on why the grouping through the establishment of development teams is the second pattern of Waterfall and Agile practice that consistently obstructs flow, effectiveness and fun. The structure of TOSD makes development teams entirely dispensable.

When the number of developers for any item at any point of time is strictly limited to a maximum of two, then this means that these soloists or tandems must also be capable of doing the job. Individuals must have sufficient mastery. Especially less experienced developers will have to be coupled with more versatile and experienced developers, and items that require special masteries will have to be matched with appropriate developers. In TOSD, this kind of coordination is not the responsibility of managers, though, but part of every developer’s work.

Create a coherent, decentralized system with an OK-Point – instead of forging ‘development teams‘

This leads us to Principle 3:

Principle 3:

All Realization work is strictly time-boxed. Realization can take 1 day, 2 days or 3 days. 1 day is ideal. Defining the time-box is part of Conceptualization. At the OK Point, the time-box must be agreed upon between Realizers and Conceptualizers.

The OK Point allows for Realizers and Conceptualizers to self-organize the development process, by consulting with each other and by agreeing about passing on an item from one stage to the other. No central coordination by managers or supervisors is necessary. Such coordination, allocation, scheduling or planning would be counter-productive, in fact. Realizers and Conceptualizers may consult managers (or the List Owner), but the rule of the game is that it’s their decision to come to an agreement, at the OK Point. Realizers are then bound by the scope outlined in the concept, and by the time-box that comes with the item - which may be 1 day, 2 days or 3 days.

Considering the combination of Principles 1, 2 and 3, it should be clear that such a development process, or system, is far more adaptive and far less obstructive than any kind of fixed development team structure, and any kind of batch processing - through Sprints or Feature teams, for instance. Through the three principles, TOSD enables timely self-organization to a maximum. It also allows organizations to match work items with developer mastery in a far more sophisticated, attuned and timely way. The combination of the three principles allows to eliminate steering, puts an end to waiting and stop-and-go processing.

So what happens with the factors that limit software development performance, which were called out by Jellyfish, based on recent research? The first, integration of non-coding development tasks, means that such tasks must to be organized in such a way that they are integrated in the flow, and are taken on by developers according to their strengths. In TOSD, non-coding tasks are fully integrated into Conceptualization (what aspects), Realization (how aspects), and the curation of the List of items (scope and granularity, see our research paper). In TOSD, the aspects that may be described as coordination and waiting times are largely eliminated, thanks to single-piece-flow, mandatory self-coordination by all team members, direct hand-offs at the OK Point, and immediate conversation when problems arise (TTEO principle). All these aspects boost immediacy and speed, eliminate waiting, and make coordinating roles, or overhead dispensable.

Software developers, overall, should be bound by a consistent system of development - not by team constellations, by Sprint-related meetings or by overhead roles like Scrum Master, PO, Product Manager or Agile Coach. They should instead be bound by a flow-oriented, time-oriented work systems, and ideally belong not to a an area or departmental structure, but to business teams in the periphery.

This notion is counter-intuitive. My AI tool of choice tells me that ”there are no serious thinkers or widely recognized arguments claiming that software is never developed by teams but always by individuals or duos. Discussions often debate optimal team size (e.g., small squads of 4–8, like Spotify’s model, vs. larger teams), or praise solo developers and duos for speed and agility on niche projects. The “two-pizza team” rule (Amazon) or pair programming anecdotes highlight small groups, but everyone agrees large-scale software—like operating systems, enterprise apps, or platforms—is fundamentally team-built.” It adds: “Proponents of solo/duo work (e.g., indie devs, some indie game creators) argue smaller units avoid coordination overhead and “truly collaborative” coding is rare, but they concede teams exist and dominate complex projects.” They should observe and think again.

The dominant thinking today, inherited from project management (“Waterfall”) and never questioned by Agilists, is that software production should be organized by bundling by highly specialized artisans - either functionally more divided (Waterfall) or functionally more integrated (Agile). In the latter kind of work structure, several sub-functions of software development would be integrated into the development team - take architecture, testing or documentation.

Ron Jeffries talks about combining every development team with a “dedicated business-side person”. who’s supposed to “guide” developers. This, again, is an idea from the age of Waterfall project management. To me, such notions no more than workarounds, not solutions – just like that plethora of coordinating, specialist, or managerial roles and rituals that Agilists around the world have allowed to emerge, since 2001. Those roles and notions of external coordination seem to assume, incorrectly, that developers are somewhat limited in their capabilities, intelligence or willingness to self-actualize. Those assumptions are flawed, of course. They amount to no more than prejudice.

So what’s the alternative to installing people who will henceforth play baby-sitters to developers? The solution, we believe, lies in the three principles of TOSD, and also in modifying our assumptions about developers and their human nature. We should assume that developers can quite naturally be considered business people who happen to develop software - regardless if they develop products for external clients or for their own organizations. Why assume that developers are somehow different or cannot be expected to be part of an organization’s business teams – the periphery, as we call it in Cell Structure Design? We should assume that developers want to understand the business, want to be part of the business, and are capable of collaborating with others in the business (including clients).

We should also assume that all developers should naturally develop into full-stack developers, of course. But that’s a matter for an other article. What matters is that we better treat developers as people who (can) understand the business and that are the business, instead of accepting departmentalization between developers and business people, with others trying to coordinate, taking on the terrible task of tamers or human interfaces.

In effect, we have to choose between two models of organizing software development: Either according to notions of Capacity orientation, with centralized decision-making and intense steering, or according to Time orientation, with fixed delivery times and highest levels of self-organization. Only the latter allows for flow and high performance (see illustration).

Combining TOSD with a decentralized cell structure is not a must. But it’s a plus, as it removes friction

In our work around Beta transformation, and decentralization with several software companies, we have seen that developers can and should be assigned to business cells in the periphery, instead of being grouped into a department or into separate “development teams”. Is such a structural transformation beyond the scope of people who carry titles like Scrum Master, PO, Product Manager or Agile Coach? Yes, it usually is. These actors can, however, advocate the change I am describing here, and take it to those who have authorization to make the appropriate changes.

The transformation we advocate is well within the scope of responsibilities of typical CTOs, business executives and CEOs. If these actors have the willpower to overcome development teams and to “reunite” development and business, by applying the principles of decentralization and Cell Structure Design, then they can achieve such a change within a few weeks, as we have proven in several company transformations. The methods exist. And we have seen it happen. The question you should ask yourself right now is: How much longer do you want the status quo of development teams stuck in capacity orientation and centralized steering to persist? What is holding you back from bringing flow, high performance, transparency and fun to development?

Some actionable advice for you

Read the Introducing Time-Oriented Software Development research paper and visit the TOSD web page to learn more about TOSD, the Pradtke case and the process of making a TOSD system real within a few weeks.

If you have authorization to work the system, get going with the other points on this list. If you do not have that authorization, take the case for change described in this article to people who have it.

Stop treating groups of developers as ‘development teams‘. This will likely include removing team metrics, targets, meetings, rituals, getting rid of coordination/steering tools like Jira, and putting an end to overhead roles like Scrum Master, POs, Product Managers, Agile Coaches.

Remove all specialized development roles. People will retain their masteries, but will stop being treated as departments-of-one. Instead nominate List Owner, Conceptualizers and Realizers, and establish the Conceptualization-OK Point-Realization logic among all developers.

Remove Sprints (or cadences, iterations) and Scaled Agile processes, roles, meetings, measures, if you have them. Substitute backlogs with one or with several Lists of Items, associate all Conceptualizers and Realizers with a single List. Go live with development in TOSD, with all developers, all at once.

Combine TOSD with decentralized Cell Structure Design, if possible.

Related reading on Time-Oriented Software Development (TOSD)

Read my article on the dysfunction of Sprints, an article on the history and conceptual underpinnings of time orientation, an article on three key patterns of time orientation and an interview about TOSD with Pradtke CTO Sebastian Kubsch.

No AI was used to generate this article’s, except the highlighted quote marked as written by an AI tool. AI was used exclusively for research and translation purposes, not for text generation.

Another gem. A compelling case for the reimagining of software development.