Time-orientation may be the Lean movement's last chance to revitalize itself

Turning towards time is an opportunity to step up the lean game everywhere. It could hold the key to transforming the business world, as intended by several generations of lean pioneers

This week is seeing the publication of the 24th BetaCodex Network research paper Slave to the Rhythm: Adopt Time-Oriented Work Systems. Now. In line with that exploration of organizational rhythm, I would like to invite you to take a deeper look at the history of the Lean movement, to appreciate more fully why time-orientation is “the missing piece” to lean transformation-that-deserves-the-name, and key to creating full-fledged lean enterprises. Regardless of an organization’s scale.

Let’s go back to the beginnings first. The surge of Lean in the early 1990s was triggered by the publication of a single, influential book, The Machine That Changed the World by James P. Womack, Daniel T. Jones, and Daniel Roos, in 1990. The book introduced the concept of Lean production to a broad Western audience and became a worldwide bestseller. What then happened was a boom period that lasted for almost two decades and that produced a thriving lean industry. At the end of the 2000s, however, Lean went into decline. Public enthusiasm around lean management began to wane, as companies realized they weren’t getting the benefits out of it they had imagined,. Only very few companies had achieved something similar to the kind of ultra-effectiveness that Toyota had reaped from Lean principles.

But the movement had taken the wrong turn long before the decline of the lean industry actually began to materialize. By the early 2000s, most lean experts, consultants and companies had already gone into tool mode, or had deflected into large-scale certifications, trainings and solutions that were way too mechanistic, too myopic and often even opposed to Lean principles, by and large. A decade after The Machine that Changed the World, hardly anyone was tackling lean as system-wide change anymore. One indicator of the deviation into fixing and piece-meal approaches was the rise of Six Sigma, which became hugely influential in lean circles after 1995. Even though the Six Sigma approach to improvement was largely antagonistic to Lean principles and clearly opposed to the systemic nature of that Toyota had done.

Lean practice: far from great

There is consensus, by and large, that today’s predicament of the Lean scene is not due to a possible irrelevance of Lean principles, but rather rooted in the limitations of popular Lean approaches within a rapidly changing industrial landscape. Listening to common reasons given for today’s lack of Lean adoption and sustainment, you will hear about lack of management commitment, a failure to align Lean with other initiatives, or insufficient workforce engagement. Look closer and you will notice that these are symptoms, not problems. And they likely hint at the same root causes.

Take the example of one of the most popular Lean approaches today: Toyota Kata. The Kata approach initially aimed at first principles of Lean, but was then turned into a large-scale certification and training business. The goals of Green Lean, another recent idea, are also laudable, but such claims provide little orientation as to how to adopt lean more profoundly and also transformationally. In the meanwhile, applicability of the greatest Lean case of all, Toyota’s TPS, has seemed more and more elusive to most companies. We examine this predicament more fully in our new research paper on time-orientation.

The question is: How can we make lean, or lean transformation systemic and system-wide - the way Toyota did it? How can we make it fast enough, and involving all functions of an organization, so that it can be coherent, and that it can stick? Because we likely do not want to spend more than three decades transforming the organization – as Taiichi Ohno and his peers did it. As you will see in our research, there are ways to undertake Lean Transformation that are so fast and inclusive that the key stage of the transformation will take just a few months. And require very few consultants.

Lean-as-a-system is never “implemented”

The problem with lean tools is that they are neither systems themselves, nor are they systemic. Which is also why they can be implemented and why they can be purchased at ease. You place a tool in a system, done. It may not produce all the impact it could produce or all the impact you wish for, but you can execute upon it.

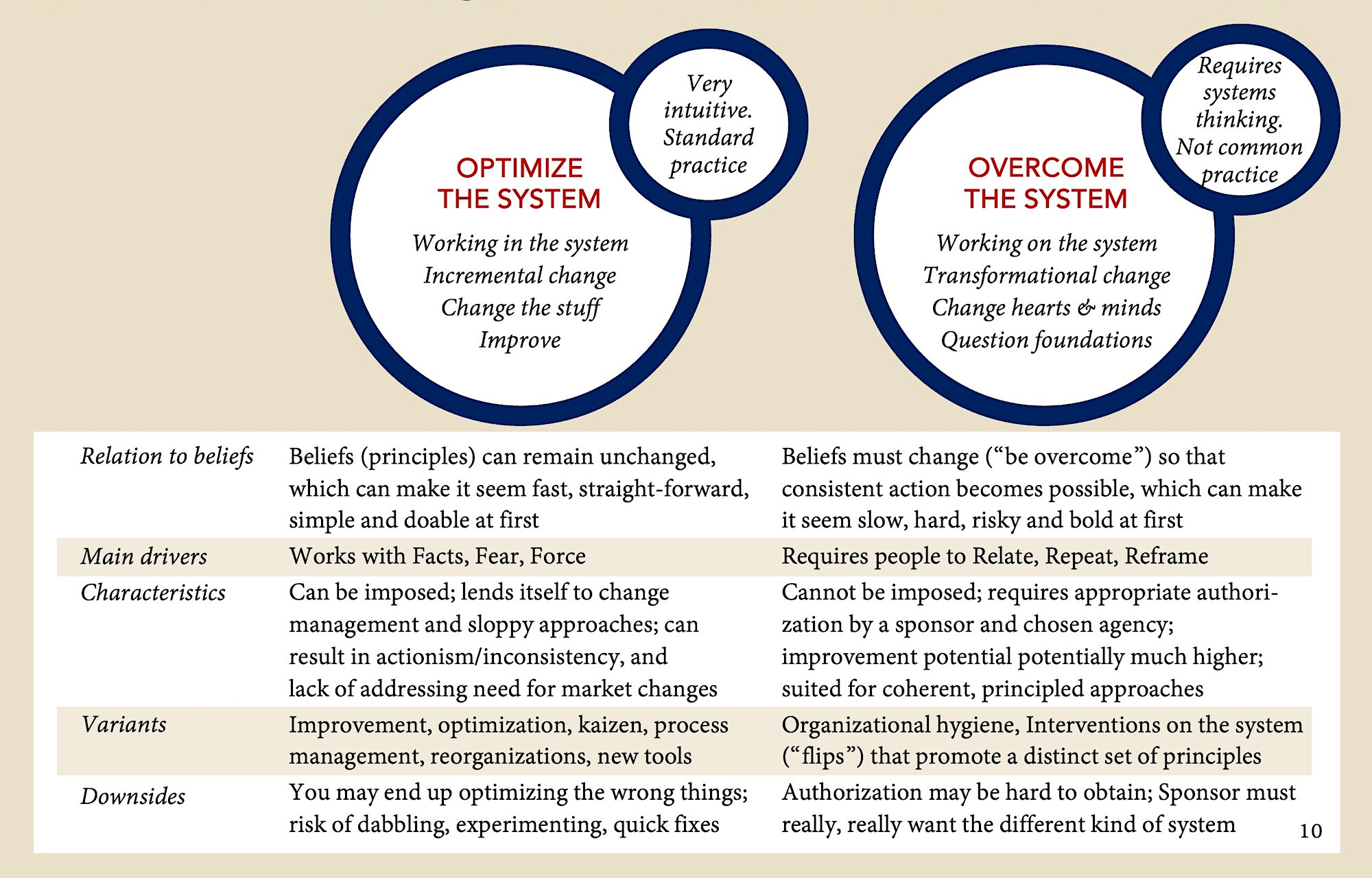

Lean-as-a-system, on the other hand, defies implementation, training, realization-through-certification, pilots, experimenting and trying. Lean-as-a-system (which is what we define as Lean here) can only be brought about by overcoming the existing system – which in current industrial reality is usually a system of batch processing, of volume-orientation, characterized by an obsession with optimization, and based management by numbers (far from the gemba). As you will see in our research, Overcoming the system from batch processing to time-orientation requires authorization and a system-wide approach. On the other hand, it is also much faster than incrementalism and implementing tools without much authorization.

Remember: It took Toyota more than three decades to bring Lean, or TPS principles, to its entire operation. No company today could afford such a slowly advancing transformation process, and no Lean transformation will ever again get that much time, and long-lasting authorization to proceed. We must achieve Lean Transformation faster. The good news is: Such transformation of organizational systems doesn’t require so much time anymore, as there we now have far more powerful methods for Very Fast Organizational Transformation at our disposal than Taiichi Ohno and his peers had. These methods of overcoming the system are also further explored in the Slave to the Rhythm white paper.

The lean movement mainly failed to live up to expectations because it never embraced contemporary organizational development, which would have allowed for robust transformation in relatively little time. Put differently: The science of change was never taken seriously by Lean thought leaders and practitioners. Existing scientific insights from fields like sociology, business administration, psychology and social psychology was thoroughly ignored. Instead, “constant experimentation” was declared to be the only stance at lean adoption – according to Lean icon James Womack, one of the authors of The Machine that Changed the World. This doctrine was reiterated by Womack as recently as 2025. In so doing, Womack and others have been over-stretching the logic of continuous improvement, applying it to transformational change, or overcoming the system. Which is a profoundly flawed idea, and a perfect example of “island rationality, overextended.”

We in the BetaCodex movement understand that to ignore existing, superior theories of change will likely lead to dabbling, stalling and failure to overcome the system. We learned this the hard way, because Beyond Budgeting movement that preceded the BetaCodex suffered from the same kind of transformative anemia as the Lean movement today. But what is behind the incessant call for experimentation? Is it a lack of insight? Is it hubris? Or is it a subtle form of nihilism?

No lean enterprise without lean transformation. But lean transformation is a coin with two sides

The lean movement, just like its agile sibling, has so far failed to acknowledge that lean transformation is a coin with two sides:

One side is lean principles, techniques and technology – which are quite well-understood, even though time-orientation as a key cornerstone seems to have been largely overlooked.

The other side is organizational development principles, techniques and technology.

You cannot “do lean” or become lean without the latter of the two sides! In short: The call to rely on experimentation for lean transformation, equals shutting out all rationality and plenty of existing scientific insight from the second realm: The realm of organizational development. To opt for such the stance of experimentation could ultimately be described as averse to scientific insight – which is rather odd for a movement such as Lean, which prides itself to be rooted in scientific thinking around systems and the logic of sound engineering. Or, to put it more positively: While early pioneers like W. Edwards Deming were fully aware of the science of systems change. I also firmly believed that Taiichi Ohno at Toyota perceived his work as much more than experimenting. Ohno was fully aware that overcoming the system required authorization, invitation, and Chosen Agency, as we call it in our new research paper. We simply have to recover the quality of insight that the lean movement’s pioneers had. We must go Deming and go Ohno again!

I am firmly convinced that time-orientation is the path forward, and the way out of the lean transformation conundrum that companies, and the lean movement as a whole, are facing today.

Read BetaCodex Network research paper No. 24

and learn about the foundations of Time-Oriented Work Systems – from TPS to the long proven Weichselbaum System, Lean RFS and Quick Response Manufacturing. Learn about how to tackle Lean Transformation that deserves the name, enriched by equally long-proven approaches such as Cell Structure Design, Relative Targets and OpenSpace Beta. Downloading all BetaCodex Network research papers is free of charge and free of registration!

Learn more about Time-Oriented Work Systems with Niels Pflaeging

Take part in my new online MasterClass on Time-Oriented Work Systems

Take part in an introductory online event on Time-Oriented Work Systems in German

Take part in a 1-day workshop with Niels about Time-Oriented Work Systems (in German)

Read an article about Lean RFS on the Red42 Substack

Watch an episode of BetaCodex LIVE about Lean RFS and “true lean” – with special guest Ian Glenday

Watch an episode of BetaCodex LIVE about W. Edwards Deming’s work

Get the print edition of the “Slave to the Ryhthm” research paper, from Red42